An occasional, unpleasant and uncomfortable night exposed to the elements in an emergency bivouac or snowhole can usually be endured without undue consequence but on extended, multi-day excursions in the mountains a good night's rest is a prerequisite to ensuring one is fit for the following day's exertions.

On popular, well-frequented routes a variety of indoor accommodation may be possible. In Scotland on a climbing tour of Wester Ross I stayed in Youth Hostels while in collecting my final Munros had a sound night's sleep in the reputedly haunted Ben Alder Cottage - one of the many bothies to be found in remote corners of the Highlands. Walkers doing the West Highland Way from Milngavie to Fort William can even stay in hotels.

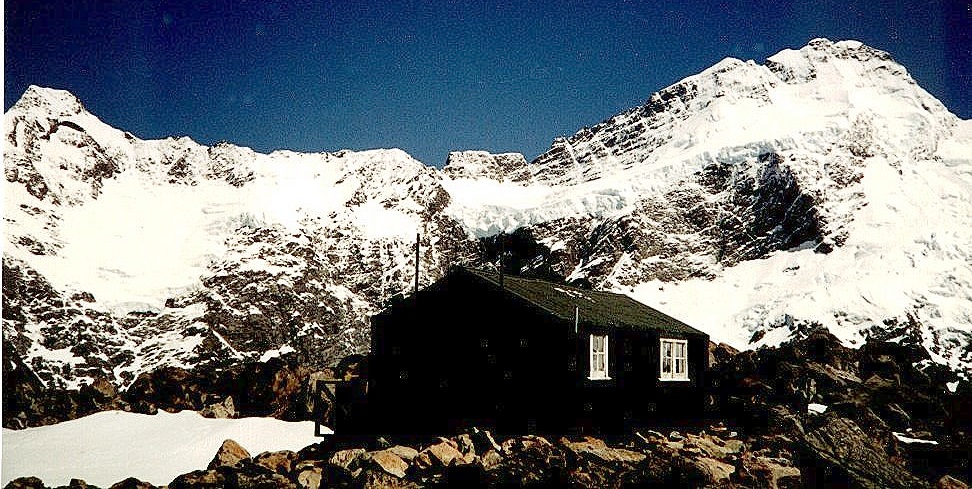

In Europe and New Zealand alpine huts ( not always an appropriate term - some so-called huts in the Austrian Tyrol are three-storied, stone-built buildings more akin to hotels ) provide stepping stones to the summits - although sometimes their approach routes can be as difficult and dangerous as the final climb. They also enable high-level tours without recourse to descents to the valley floor.

In the Nepal Himalaya the tea-shops established to meet the needs of the traditional porter system for carrying trade goods have mostly been converted to lodges for the use of today's independent trekkers. Additionally the number of new, purpose-built lodges has mushroomed since my first visit 12 years ago and although quality is now comparable with alpine huts the overall level of hygiene, sanitation and cleanliness still leaves much to be desired. There is nothing worse than an attack by bed or stomach bugs to ruin a night's rest or completely spoil a trek or climbing expedition.

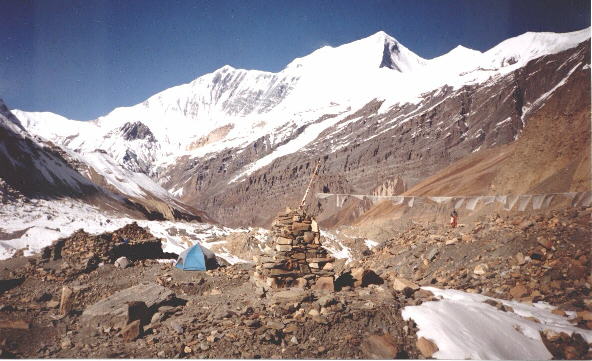

The alternative, which I much prefer to communal bunkhouse or dormitory type accommodation, is to use a tent. On my camping treks in the Nepal Himalaya my tent, like an Englishman's home, is my castle used not only as a bedroom, dining room, office for route planning and book-keeping, but my personal sanctuary where I can zip the door to obtain privacy from the prying eyes of curious children, porters or other trekkers. Carrying one's own tent also enables access to remote, uninhabited wilderness areas beyond the reach of tea-shop treks such as the secluded Hidden Valley on the Dhaulagiri Circuit and the beautiful Chhuling Valley beneath the Rupina La.

However camping is not without its trials and tribulations.

An ability to disregard assorted sounds emanating from the great outdoors is an essential attribute but in the Tamang village of Tibling in the Ganesh Himal the unheeded rustlings in the grass were made by sneak thieves who slashed the side of my tent with a razor blade and made off with my first aid box and a stuff bag containing most of my clothes.

Encamped at Gokyo in the Solu Khumbu during the freak storm of November 1995 I was lucky to escape from my tent before it collapsed under the weight of snow. Memories were revived last autumn in the remote yak pastures of Thare Teng when we were again caught in a prolonged, two-day blizzard but this time hourly patrols throughout the night to brush the snow off our tents overcame the problem.

Backpacking around the South Island of New Zealand the weather was even more changeable than in Scotland with frequent depressions blowing in from the Tasman Sea. In the White Horse campsite beneath Mt.Cook the arrival of the next squall was heralded by the howling of the wind through the surrounding trees. One particularly violent gust whipped my flysheet clean away. Several sleepless nights were spent holding onto the tent poles. My ice-axe came in useful as an entrenching tool. Even for non-climbing, camping treks in the Nepal Himalaya ice-axes are an indispensable item for this purpose and also making fire-places and excavating grease and toilet pits.

Animals can be another hazard.

Returning from a climb in the Matukituki Valley to the south-west of Mt.Cook I found my tent had been trampled and torn by a herd of cows while in the Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado something chewed a hole in the groundsheet and gorged itself on a loaf of bread. In National Parks such as Yosemite black bears cause thousands of dollars worth of damage each year and warnings against storing food in tents are posted in campsites.

Trying to erect my tent in Death Valley I found it impossible to fit the flysheet over the ridgepole which had expanded in the sweltering heat while the fabric had shrunk. At the other temperature extreme the coldest night I have endured under canvas was a bone-biting -25 degrees C. at the Panch Pokhari at the head of the isolated Hongu Valley in the Everest region. It was more severe than at high, snow camps on Mera Peak and on the Trashi Labtse high pass. As in the glens of Scotland it can be colder in the valley floor than on the surrounding mountainsides.

However such tribulations have been far outweighed by the many more pleasurable experiences enjoyed - especially some of the spectacular views obtained in the evenings and mornings from my tent door such as the glorious sunset on Loch Hourne when camped in Barrisdale Bay, the desert sky in the sub-Sahara beneath the High Atlas or from Dhaulagiri Base Camp of the great avenue of 7000metre peaks towering above the Chonbarden Glacier.

( The Commentator, The (Glasgow) HERALD Saturday 26th June 1999 )